Introduction

This article is meant to provide a reader an intuition and deeper understanding of the thought process for implementing an arbitrage prediction system. There are many approaches to arbitrage with decentralized finance. In this paper we will mostly focus on a specific approach involving two exchanges for Uniswap v3 compatible exchanges [1].

Background

Arbitrage [2] in financial systems is prevalent, expected, and well known in industry. Likewise, decentralized finance (DeFi) is transforming into a significant component of the global financial ecosystem. With that end in mind, the United States is considering major steps to protect and enable citizens to integrate with these ecosystems in a responsible way in the future [3]. The current global interest and the potential opportunity to enable a new form of retail trading brings us to this effort: create a system to perform a basic arbitrage detection / recommendations on Uniswap v3 compatible Liquidity Pools.

For the goal of implementing an arbitrage forecasting system, there are many internet resources that are searchable online. Two white papers that influenced our work are [4][5]. In [4], the author creates and analyzes a binary classification detector and compares results from various model types, etc. In [5], the authors provide a theoretical framework to support N-exchange arbitrage and proceed to perform analysis of past transactions on the block chain to understand the opportunities. The authors do not actually describe their model techniques.

Specifically in the Ethereum ecosystem, Automatic Market Maker (AMM) Liquidity Pools [6] allows price changes to be managed through a series of relatively simple controls.

Basic Principles

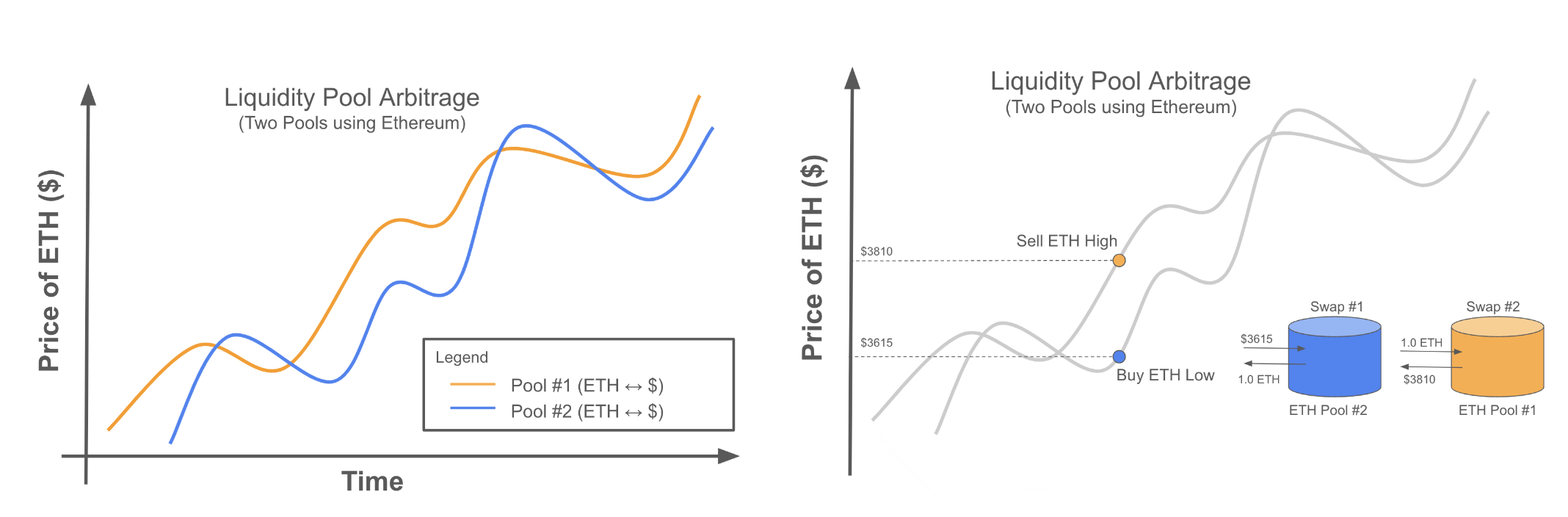

The ingredients for performing arbitrage include some very basic concepts: (1) buy low, (2) sell high. For Liquidity Pools, the idea is implemented through swaps on multiple exchanges (in this case two).

Figure 1: (left) Two exchanges over time (Ethereum / US Dollar pair), (right) example of a two exchange arbitrage resulting in $195 of possible arbitrage benefit.

After we are able to observe a price discrepancy that could be able to be used for arbitrage, we need to consider the costs to perform the trade we desire. As any financial exchange there are fees [7] involved that need to be taken into account. The first fee is referred to as “gas fees”, which is an Ethereum specific term for the cost to run a transaction (i.e. swap in this case) on the decentralized network. There are many elements to gas fees, but generally, each swap induces a fee (i.e. two fees to track). There is a great deal of interest in predicting gas fees and there are many resources that share data on global fees across a range of Ethereum contracts, etc [8]. The second fee considered is the transaction fee (also known as liquidity provider fee), which is a fee based on the percentage of the token being exchanged. In Uniswap v3, there are fee tiers [9], which are determined by each exchange and can be one of three values: 0.05%, 0.3%, and 1%.

With price observations and fees outlined, next we will construct a basic theoretical approach for detecting arbitrage opportunities.

A Basic Prediction and Minimum Investment Strategy

All combined, this basic approach looks like the following:

PA = (1-FTH) x PH- (1-FTL) x PL - FG

Where:

PA - Arbitrage Profit Price

PL - Pool with Lower Token Price

PH - Pool with Higher Token Price

FTL - Transaction Fee for Pool with Lower Token Price

FTH - Transaction Fee for Pool with Higher Token Price

FG - Gas fees for both pools (based on demand on the network)

How do we create a forecasting algorithm around this idea when the idea is that an investor is going to invest some amount other than the token price itself? Our team has decided to use a Regression model to predict a percentage change of the price between Pool 1 and Pool 2. This in reality leads to two forecasting models (one for Gas Fee prediction and one for Percent Change between pools).

With this in mind, the equation now changes to:

PA = (1-FTH) x P0 (1 + ΔP) - (1-FTL) x P0 - FG

Where:

P0 - Initial Investment

ΔP - Percent difference in price between Pool 1 and Pool 2 or (P1-P2) / min(P1,P2)

FTL - Transaction Fee for Pool with Lower Token Price

FTH - Transaction Fee for Pool with Higher Token Price

FG - Gas fees for both pools (based on demand on the network)

With a baseline theory to describe arbitrage, we set PA to zero to attempt to derive the minimum investment amount to overcome gas and transaction fees. We solve for P0 (referred to below as Pmin) given PA = 0. Rearranging rearrange the previous equation results in:

Pmin > FG / [ (1+ΔP) x (1-PTH) - (1-PTL) ]

Where:

Pmin - Minimum Initial Investment

ΔP - Percent difference in price between Pool 1 and Pool 2 or (P1-P2) / min(P1,P2)

FTL - Transaction Fee for Pool with Lower Token Price

FTH - Transaction Fee for Pool with Higher Token Price

FG - Gas fees for both pools (based on demand on the network)

Risks

Much like any investment strategy, there are always risks. In this section, three risks in particular will be discussed: (1) Model Error, (2) Slippage, (3) MEV Actors.

Model error refers to the uncertainty of the predictions of an operationalized models. One approach to model error is to attempt to put confidence intervals on the model predictions with something like [11], which could be applied in a Regression context.

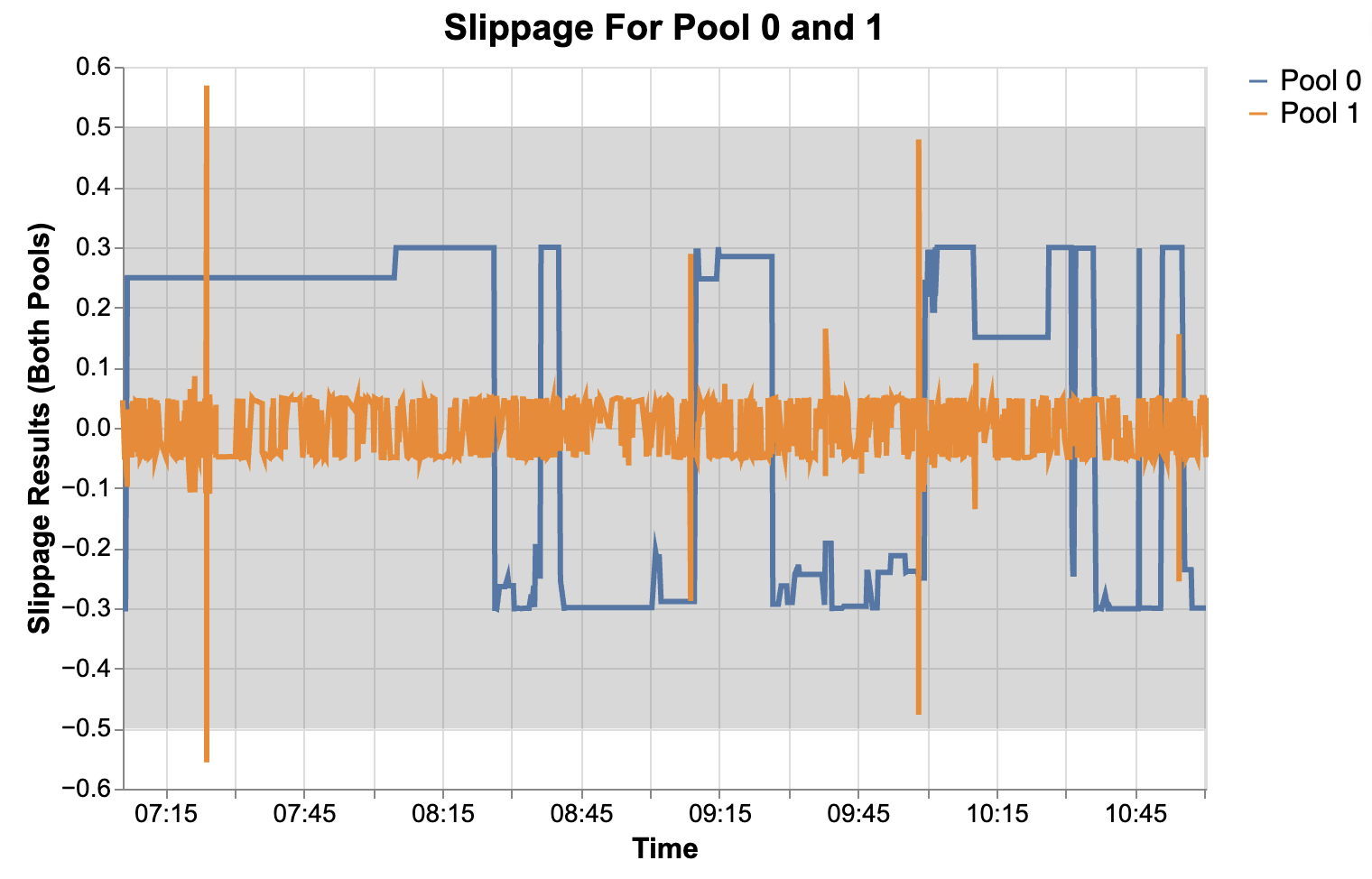

Slippage refers to the Ethereum concept of price changing after a swap is initiated but prior to finalizing / validating the EThereum block. In Uniswap, this ‘slip’ is guaranteed to be less than 0.5% by default [12], but in general, the user (or the user app) can override that to change the range from 0.1 to 5% [13]. The model we create can calculate an estimated bound on the transaction based on typical pool conditions (i.e. for WETH-USDC / 0.05% fee tier, the slippage amounts are typically around 0.3%).

Figure 2: Slippage Observations for Pool 0 - WETH/USDC 0.05% fee tier, Pool 1 - WETH/USDC 0.3% fee tier. Grey box is the range of 0.5% (default).

MEV stands for Maximal Extractable Value. As an intended component of Ethereum, there are techniques for executing the decentralized exchange to generate more money for what is referred to as validators [10]. Essentially, MEV actors are able to take your transaction submission prior to finalizing the request and reorder it to benefit themselves (i.e. other terms for these types of actions include back running or front running or sandwich attacks). This has the risk of reducing your own benefit from a swap you have predicted. It may be possible to estimate how much harm could be done from MEV actions (i.e. if the transactions prior to the swap affect the volume of the pool enough, the price change could impact the original arbitrage detection calculus). Things like sandwich attacks and back running are mitigated some by slippage limits that are put on transactions. i.e. if the price is manipulated too much the block performing the validation can be cancelled.

References

[1] https://uniswap.org/

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arbitrage

[4] Okasová, Kristína & Kostal, Kristian. (2024). Using Machine Learning for Predicting Arbitrage Occurrences in Cryptocurrency Exchanges.

[5] Robert McLaughlin, Christopher Kruegel, and Giovanni Vigna. 2023. A large scale study of the Ethereum arbitrage ecosystem. In Proceedings of the 32nd USENIX Conference on Security Symposium (SEC ‘23). USENIX Association, USA, Article 185, 3295–3312.

[6] https://docs.uniswap.org/contracts/v1/guides/pool-liquidity

[7] https://ethereum.org/en/developers/docs/gas/

[8] https://milkroad.com/ethereum/gas/

[9] https://uniswap.org/whitepaper-v3.pdf. See Section 4 - Governance.

[10] https://ethereum.org/en/developers/docs/mev/

[11] Angelopoulos, Anastasios N., and Stephen Bates. “A gentle introduction to conformal prediction and distribution-free uncertainty quantification.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.07511 (2021)